In their legal initiatives regarding trading platforms for DLT-based securities, Switzerland and the EEA are taking a very progressive approach. The Swiss DLT Law introduced a new type of financial market infrastructure license for trading platforms for DLT-based securities.

Entities without a pre-existing financial market license may apply for this new type of license. Applicants expecting a business volume below certain thresholds qualify for a sandbox solution and benefit from less strict requirements. In contrast, the European Commission proposes a pilot regime to test the waters before introducing wide-ranging changes to the EEA financial market regulation. Under this pilot regime MiFID II investment firms, market operators or CSDs may apply for a permission to operate a DLT financial market infrastructure. Experiences gathered during this pilot regime will be analysed and reported to the EU Council and Parliament at the latest after a five-year period. Subsequently, more permanent and extensive legislative action will be taken.

Despite the different approaches, both legislative initiatives aim at grasping the opportunities brought by DLT related to activities traditionally reserved for CSDs and trading platform operators. Both Switzerland and the EEA introduce a possibility to combine these activities under one financial market infrastructure, that keeps DLT-based securities in central custody, enables multilateral trading, and settles transactions.

Switzerland

The new type of financial market infrastructure introduced by the Swiss DLT bill is named “DLT trading facility” (DLT-Handelssystem). A DLT trading facility is a commercially operated institution for multilateral trading of DLT securities. Its purpose is the simultaneous exchange of bids between several participants and the conclusion of contracts based on nondiscretionary rules. To clearly differentiate the DLT trading facility from the multilateral trading facility (MTF), one of the following requirements must be met in addition: (i) Admission of legal entities other than supervised financial institutions or private clients as participants; (ii) provision of central custody of DLT securities based on uniform rules and procedures; (iii) provision of clearing and settlement for transactions in DLT securities based on uniform rules and procedures.

In addition to multilateral trading of DLT securities, the DLT trading facility may also offer trading of instruments not qualifying as securities, such as cryptocurrencies. However, according to the draft DLT ordinance, derivatives in the form DLT securities, instruments which impede compliance with anti-money laundering provisions (e.g. privacy coins), or instruments that could impact the integrity or the stability of the financial system are not eligible for being admitted to trading.

Compared to a traditional stock exchange or MTF, a DLT trading facility has two major regulatory advantages:

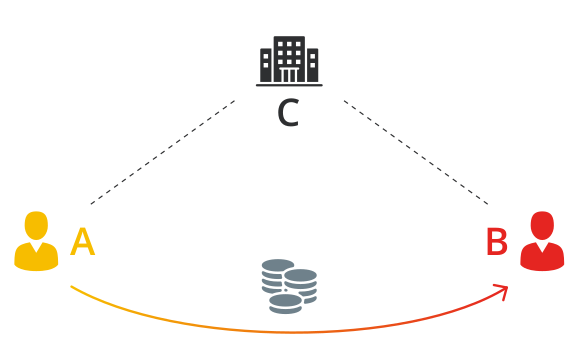

First, a DLT trading facility will be allowed to admit not only regulated financial intermediaries as participants but also other legal entities and private clients. The latter two, however, can only be admitted, if they trade in their own name and on their own account. This is to facilitate the combat against money laundering and terrorist financing. To enable the Swiss Financial Markets Supervisor Authority (FINMA) to fulfil its duties, all participants, whether subject to FINMA supervision or not, will have to provide it with information or documentation upon request.

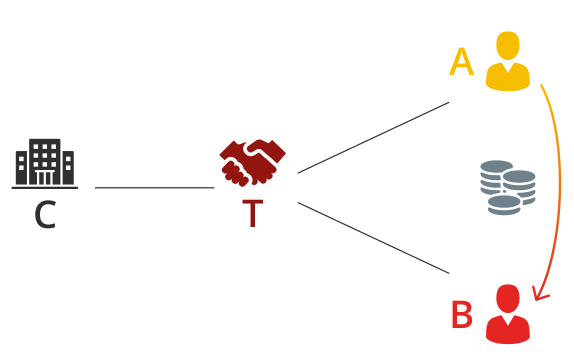

Second, a DLT trading facility will be allowed to provide central custody, clearing and settlement services for DLT securities, e.g. on a blockchain. This is a major innovation since MTFs and stock exchanges are currently dependent on a CSD to fulfil these functions. A DLT trading facility will, however, not be allowed to centrally clear DLT securities, to avoid a risk concentration. This activity remains reserved to central counterparties.

The requirements to obtain an authorisation as a DLT trading facility will be similar to the ones for obtaining authorisation as a stock exchange or MTF. Additional requirements, similar to the ones imposed on CSDs, apply if the DLT trading facility is not only enabling multilateral trading, but also keeps DLT securities in central custody or clears and settles transactions.

DLT trading facilities must be operated by a Swiss entity, save for the possibility to outsource certain services. In other words, a completely decentralised trading platform will not be licensed as a DLT trading facility in Switzerland. Other noteworthy requirements are for example the establishment of a self-regulation and supervisory organisation that is independent from the business functions. This organisation has to ensure, inter alia, fair and open access to the DLT trading facility as well as orderly and transparent trading. The minimum capital requirement is CHF 1 million.

DLT trading facilities providing central custody, clearing or settlement services on top of enabling multilateral trading are subject additional requirements. These include for example requirements related to the segregation of assets, establishing procedures for the case of a participant default, risk diversification, liquidity and collateral requirements. The minimum capital requirement for DLT trading facilities with such additional CSD functionalities is CHF 5 million.

To encourage start-ups and smaller institutions to advance innovation, the DLT bill includes a sandbox regime for small DLT trading facilities. According to the draft DLT ordinance, a DLT trading facility qualifies as small if its trading volume in DLT securities is less than CHF 250 Million p.a., the volume of DLT securities kept in custody is less than CHF 100 million, and the clearing and settlement volume is less than CHF 250 million p.a. Small DLT trading facilities can benefit from several eased requirements. These eased requirements namely aim at reducing the required headcount and organisational burden. The draft ordinance sets the minimum capital requirement for small DLT trading facilities at CHF 500’000 and for small DLT trading facilities providing custody, clearing and settlement services at 5 % of the DLT securities kept in custody, but at least CHF 500’000.

European Economic Area

The proposed PDMIR pilot regime for market infrastructures based on DLT aims at gathering evidence and experience before introducing wide-ranging and permanent changes to the existing financial services legislation. Thus, operators of DLT market infrastructures will need to provide the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA) and the national competent authority every six months with a report on their activity, including the difficulties and issues encountered. ESMA will fulfil a coordination role between the national competent authorities and evaluate the outcome of the pilot regime on a yearly basis. ESMA and the European Commission will report to the Council and the Parliament at the latest after a five-year period, whereupon further legislative action will be taken.

A DLT market infrastructure according to the PDMIR is either a DLT multilateral trading facility or a DLT securities settlement system. The permissions to operate either type of DLT market infrastructure are granted by the national competent authority, which is required to consult ESMA before deciding on an application. A permission is valid for no longer than six years. Only investment firms or market operators according to MiFID II are eligible to operate a DLT multilateral trading facility, while only CSDs according to the CSD Regulation can operate a DLT securities settlement system. In other words, for now the DLT market infrastructures are expected to be largely operated by incumbents, which are already licensed as investment firm, market operator, or CSD today.

The investment firms, market operators or CSDs applying for a permission to operate a DLT market infrastructure need to submit to their national competent authority, inter alia, a detailed business plan describing how they intend to carry out their services and activities, describe the use of DLT, describe their IT and cyber arrangements, and establish a transition strategy. The latter must describe the operator’s strategy to transition or wind down its business activity in case the DLT market infrastructure cannot operate as intended, for example if the permission is withdrawn.

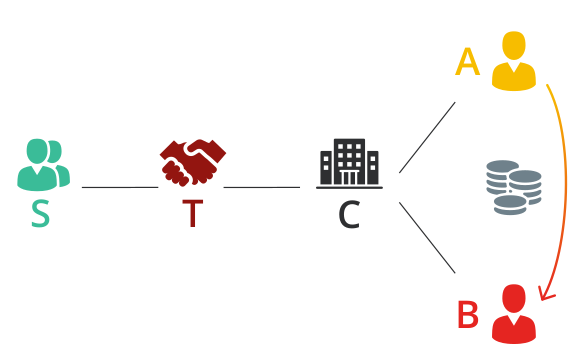

As a matter of principle, the requirements for operating a traditional MTF or CSDs apply to operators of a DLT market infrastructures as well, but the national competent authorities can grant exemptions upon request. Such exemptions will enable operators of DLT market infrastructures to make use of the opportunities brought by DLT. Most notably the operator of a DLT multilateral trading facility may request an exemption from the requirement to record DLT transferable securities in book entry form, and to only admit to trading DLT transferable securities that are registered with a CSD. These exemptions may only be granted, if the DLT multilateral trading facility (i) ensures the recording of DLT transferable securities in a way that allows for a prompt segregation of assets, (ii) settles transactions in DLT transferable securities against payment, (iii) provides timely settlement information and transaction confirmations, and (iv) guarantees safekeeping of the DLT transferable securities, related payments and collateral. A CSD operating a DLT securities settlement system may apply for exemptions from requirements of the CSD Regulation, such as the requirement to enter dematerialised financial instruments in book entry form, maintain securities accounts, and segregate participant assets in the way set-out in the CSD Regulation. Exemptions will only be granted if the operator of the DLT securities settlement system will demonstrate that the distributed ledger used is able to compensate non-compliance with the CSD Regulation requirements. Moreover, the operator of a DLT securities settlement system may also apply for being allowed not only to admit regulated entities as participants, but all types of legal and natural persons. Such persons may, however, only be admitted, if they are fit and proper, of good repute, and understand post-trading and the functioning of DLT well enough.

The PDMIR proposal furthermore puts in place safeguards to ensure that the pilot regime does not pose a threat to the financial stability. Operators of DLT multilateral trading facilities can only admit to trading and operators of DLT securities settlement systems can only record DLT transferable securities that are either (i) shares of an issuer with a market capitalisation of less than EUR 200 million or (ii) bonds with an issuance size of less than EUR 500 million. Sovereign bonds may not be admitted to trading or recorded at all. Furthermore, the total market value of DLT transferable securities recorded on the DLT securities settlement system or the DLT multilateral trading facility must be lower than EUR 2.5 billion. Operators of DLT market infrastructures will need to submit a monthly report on the adherence to these restrictions to the national competent authority.

Conclusion

The Swiss DLT bill and the draft EEA PDMIR provide a remarkable opportunity to improve efficiency of multilateral trading, central custody, and transaction settlement.

The draft status and the pilot regime approach of the EEA PDMIR will for now deter some market participants from taking action to become a DLT market infrastructure. Moreover, incumbents have a substantial advantage over challengers under the EEA PDMIR, since they already passed the hurdle of being licensed as a MiFID II investment firm, market operator or CSD, which is a requirement to be eligible for applying for the permission to operate a DLT trading facility. Switzerland’s DLT bill, in contrast, is finalised and the complementing ordinance is well advanced. This already provides enough regulatory certainty to plan and execute the first steps to become a DLT trading facility. Moreover, the sandbox solution for small DLT trading facilities is a sensible approach to reduce entry barriers for challengers.

The introduction of ledger-based securities in Switzerland provides legal certainty and allows for more efficiency in recording and transferring securities. In the EEA issuers will need to assess whether securities may be validly issued using DLT based on the laws of the relevant member state.

Although regulatory initiatives provide the legal foundation for innovation using DLT, it remains to be seen which requirements will pose challenges in practice and whether market standards for the use of DLT in this area will be developed soon. In addition, it is currently uncertain whether the regulation of DLT-based securities and DLT trading platforms will eventually be coordinated internationally through international standards or regulatory guidance. In particular, the work of the International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO) on this topic will need to be monitored.

This article is an extract from the 90+ page Security Token Report 2021 co-published by the Crypto Research Report and Cointelegraph Consulting, written by thirteen authors and supported by Crypto Finance, Blocklabs Capital Management, HyperTrader, Ten31 Bank, Stadler Völkel Attorneys at Law, Riddle&Code, Coinfinity, Bitpanda Pro, Tokeny Solutions, AlgoTrader, and Elevated Returns.