One of the main criticisms of cryptocurrencies is their volatility, which makes them difficult to use in everyday life. However, fiat currencies such as the Swiss franc suffer from a long-term problem that harms the national economies in various ways and would make the currency non-viable in a free market. This article takes a closer look at the behavior of the Swiss central bank in recent decades in regard to this topic.

Historically, the Swiss franc was a safe haven currency, but not anymore. Now, they are barely better than euros and U.S. dollars. Central banks, including the SNB, are mandated by the laws of their countries to keep the value of their currency “stable”. This is because currencies that are volatile are not good units of account. Countries that rely on unstable currencies have lower economic growth, and eventually, companies and individuals switch to other currencies, because people lose trust in the currency.

A financial crisis of trust or confidence occurs when people lose trust in a currency’s purchasing power. When people stop demanding a currency and switch to another currency, the currency’s purchasing power depreciates. If central banks continue to print during this time, a hyperinflation can occur.

As Philipp Bagus and David Howden pointed out in the paper, “Central Bank Balance Sheet Analysis”, the two main factors that contribute to people’s perceptions of a currency’s purchasing power are the quantity and quality of the reserves backing the asset. Like any bank, the SNB has a balance sheet. The SNB balance sheet has two sides: assets and liabilities.

- Assets are what the SNB buys including foreign currency and gold for its reserves, and the debt of commercial and state-owned banks.

- Liabilities are what the SNB uses to pay for the assets including notes and coins in circulation that it can “issue” or “print”, money that commercial and state-owned banks are required to keep on deposits at the central bank, money that government entities hold at the central bank, money that international organizations like the IMF hold there, debt obligations like certificates of deposits and so forth.

The stability of the currency is measured by domestic price inflation. A national currency is considered stable when there is less than 2% inflation per year. However, real stability is when and the real price (not nominal) of goods and services is stable over time. A national currency is considered unstable when the real price of goods and services is always changing. Another indicator of currency stability is its exchange rate against a major currency, for example, the US dollar or Euro. However, this indicator is not trustworthy when there is not a free market in central banking. Central banks around the world have been heavily devaluing their currencies in unison for the past fifty years. Therefore, exchange rates have been substantially more stable than they would have been otherwise despite enormous increases in the costs of goods and services in real terms. In 2000, the high of the USD and CHF exchange rate was at 1.8 CHF per USD. The dollar lost almost half of its value against the Swiss Franc in the past twenty years.

If the central bank buys securities from UBS, they create money out of thin air and credit UBS account that is held at the central bank. The newly created money shows up as a liability on the SNB’s balance sheet and it is offset with the securities they purchased from UBS.

If the central bank deposits low quality assets as backing for the newly issued money, then traders expect that currency’s exchange rate will decrease. This means that that the currency will depreciate or trade at a discount to other currencies with better quality reserves.

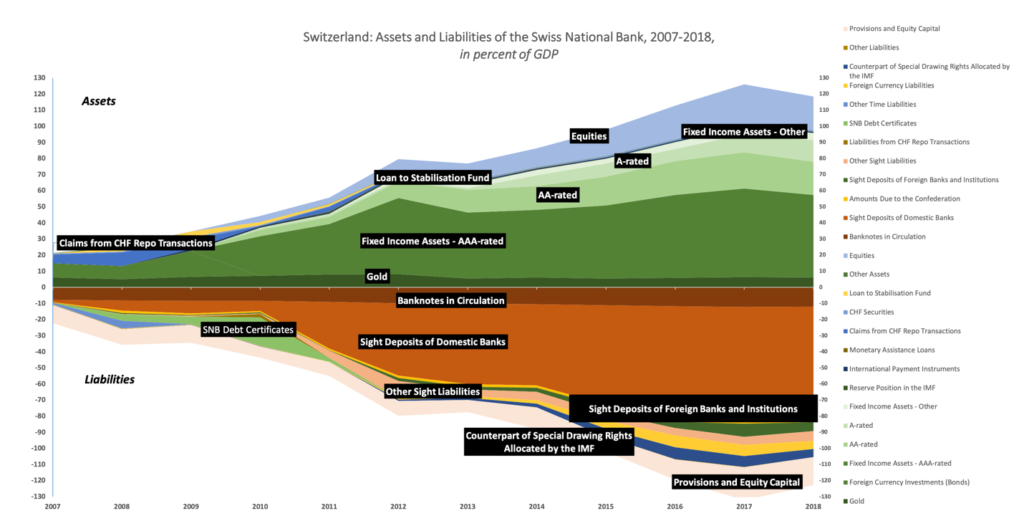

Every year, the SNB publishes its annual report in which it discloses its assets and liabilities. The SNB balance sheet for the last 13 years – compiled from its annual reports and scaled by the country’s nominal GDP as calculated by the Swiss Federal Statistical Office – is summarized in the chart below. For illustrative purposes, assets are presented as positive numbers (a “purchase”) and liabilities as negative numbers (a “payment”).

Figure 1: SNB Assets and Liabilities as a Percentage of Swiss GDP (2007 – 2019)

Source: SNB, CryptoResearch.Report

From the chart, we can see that the assets and liabilities of the SNB expanded in response to the crisis beyond Switzerland’s annual GDP. Prior to the crisis, the SNB’s balance sheet was the same size as 20% of Switzerland’s annual production. The balance sheet has swelled by a multiple of six and is now greater that Switzerland’s total annual production. Although the balance sheet’s assets have increased, looks can be deceiving. The quality of the assets on the balance sheet have decreased. Instead of relying on AAA-rated bonds, the central bank has increasingly purchased risky AA-rated bonds, A-rated bonds, and overpriced equities.

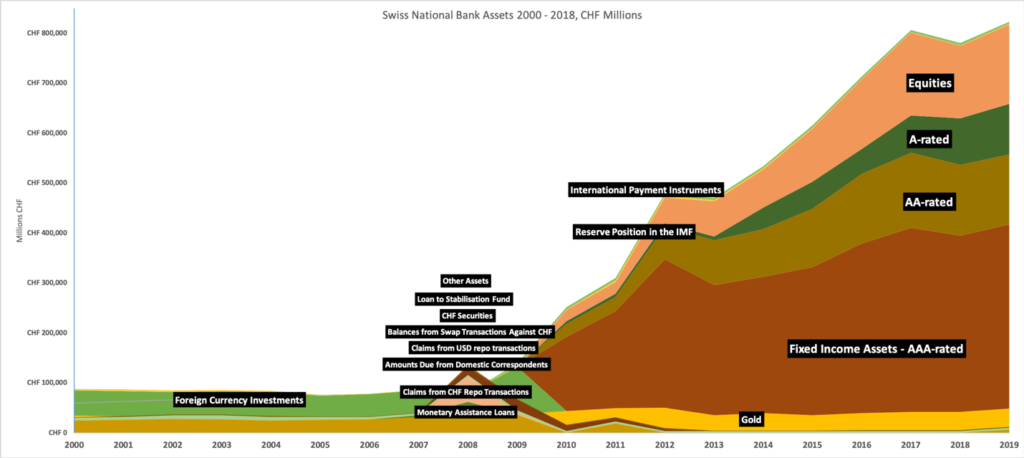

Figure 2: SNB Assets and Liabilities as a Percentage of Swiss GDP (2007 – 2019)

Source: SNB, CryptoResearch.Report

Although a central bank is mandated to keep inflation low and steady, the central bank is also supposed to support economic growth. Although, central banks are supposedly independent from politicians, they often succumb to political pressure to inject money into the economy in order to keep people optimistic and happy with the politicians in office. As Former Chief Economist of the U.S. Commodities Futures Trading Commission so succinctly puts it, central banks are tasked with squaring a circle,

“On the one hand, a central bank needs to create more money, channel it to the commercial banks, and “encourage” the banks to lend it to companies. But companies need to earn enough to pay interest and taxes, so they have to raise prices at least somewhat, which will show up as inflation and make the central bank reduce the amount of money that goes to the banks and so on.”1

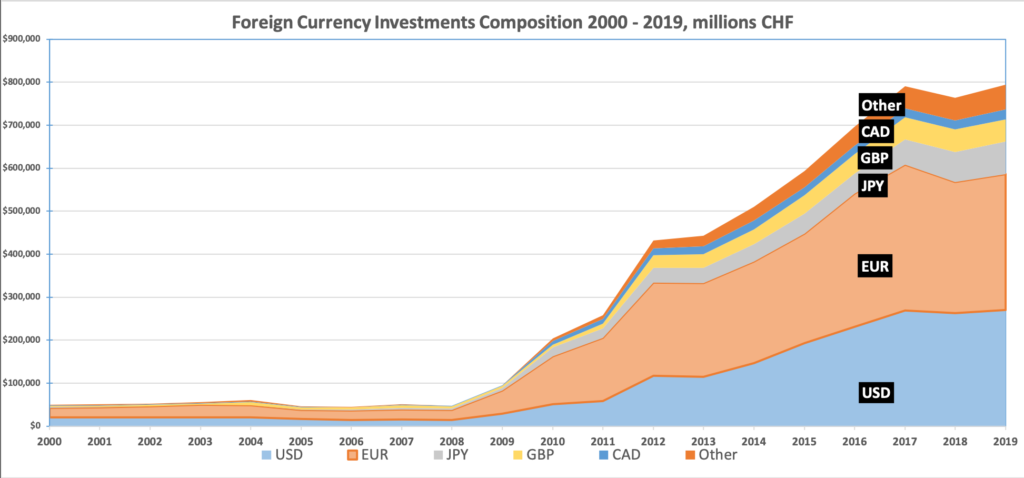

Figure 3: Growth of SNB Foreign Currency Investments 2010 through 2019

Source: SNB, RealUnit AG Schweiz

The SNB’s balance sheet consists of currencies that are issued by highly indebted countries that are systematically losing value each year due to inflation, and the SNB has been heavily printing money since the 2008 banking crisis in order to keep the economy humming along. However, this is not sustainable. The stock, debt, and housing markets have absorbed large portions of the newly printed cash increasing the inequality gap between capital holders and non-capital laborers.

The problems that the Swiss franc is facing are not a peculiarity of the franc, but something that can be observed with all other major national currencies. It can therefore be said that although the Swiss franc would probably not survive in a free market, he wouldn’t be alone in this.

1 https://voxukraine.org/en/how-ukraines-central-bank-wrecked-the-countrys-nascent-economic-recovery-in-2011-and-why-it-should-not-do-it-again/