“Blockchain technology can achieve what governments wanted to achieve for a long time: a fair, secure and attractive capital market for start-ups, SMEs and investors.”

Christian Meisser, LEXR AG

Key Takeaways

- Tokenization seems to be interesting for small and medium-sized enterprises, as the cost of raising capital via tokens is sometimes lower than on the traditional capital market.

- The regulatory classification of whether an issued token represents a security has far-reaching implications and is of the utmost legal relevance. The assessment of whether a token is to be treated like a security under supervisory law is fundamentally different in various jurisdictions.

Capital Flows to the US

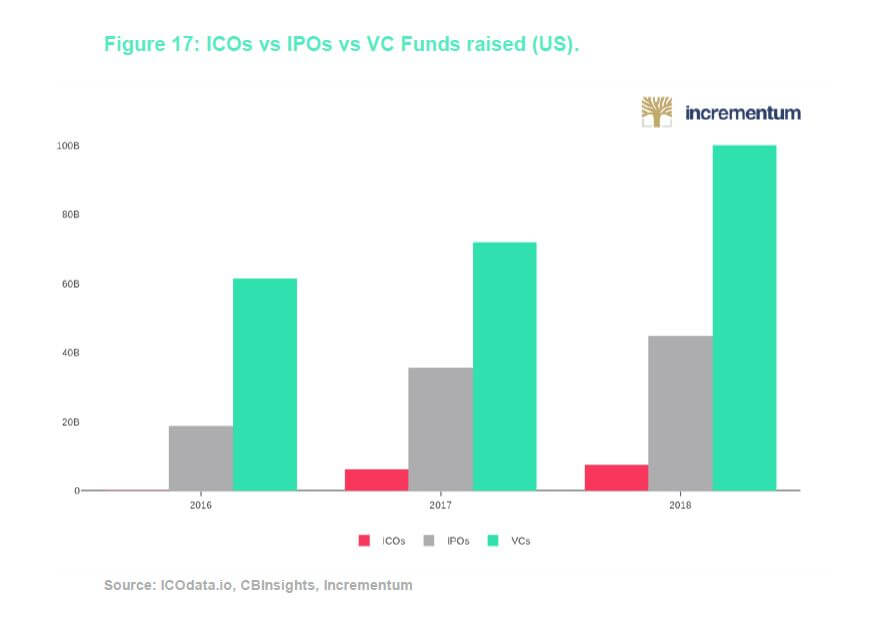

Start-ups as well as small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) are praised for being a driving force of economic growth. In principle, Europe offers excellent conditions for growth, with a mobile and well-educated talent pool, a huge domestic market, and modern infrastructure. Nevertheless, risk capital for start-ups is scarce and promising start-ups move abroad. According to a press release of the European Commission,[1] in 2016 venture capital providers invested only € 6.5 billion in the entire EU, just about one sixth of the € 39.4 billion invested in the US. According to the same release, only 26 European companies were regarded as “unicorns” at the end of 2017 (unlisted companies with a theoretical market capitalization in excess of $ 1 billion), while 109 such companies existed in the US and 59 in China.

Not only start-up funding but also financial market support for SMEs appears to be lacking. One reason why start-ups are left wanting is widely considered to be the lack of “exit” opportunities in the form of listings: in 2017, the number of European IPOs of SMEs was still down 50 percent from the time prior to the financial crisis.[2]

With public markets for SMEs weak, venture capital firms hesitate to invest in SMEs at all. While the EU tries to improve the situation with subsidies, harmonization of capital markets and mild deregulation, the world of start-up funding is fundamentally changing because of the blockchain technology. The possibility of transferring assets directly between two parties without intermediaries enables an enormous simplification of issuance and trading of capital market instruments. Thus, start-ups raised $ 5.5 billion worldwide in 2017 by issuing tokens in the framework of ICOs – and this year the total amount has already swelled to $ 14.3 billion.[3]

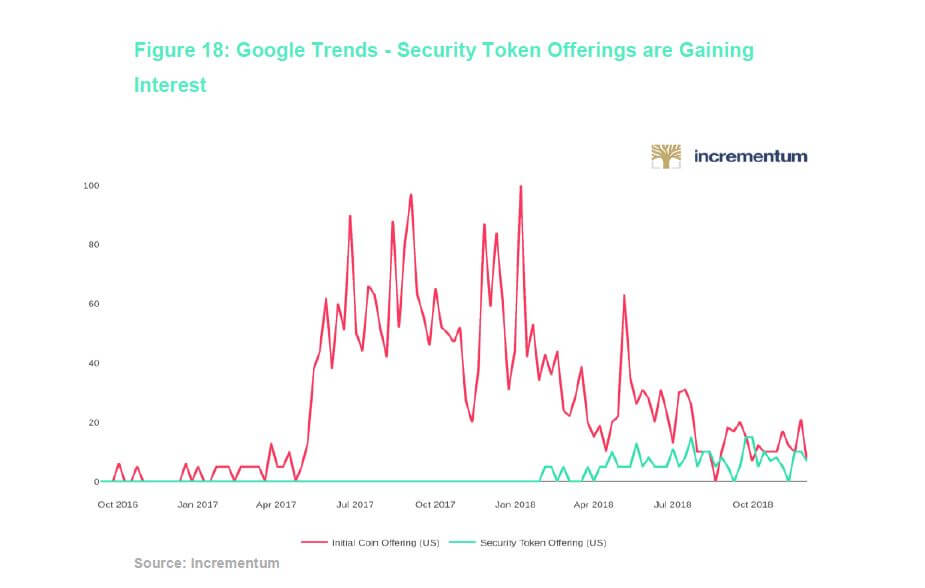

But not only primary markets (i.e., the initial issuance of ICOs) are thriving. Daily trading volume in tokens in secondary markets amounts to several billion USD.[4] Thus, blockchain technology has already furnished impressive proof of its application potential in capital markets. From the perspective of investors, it was evidently worth the risk – according to one study, the average return on investment on ICOs stands at 82 %.[5] However, the legal design of such tokens as this new technology emerges has received little attention so far and investors rarely enjoy enforceable rights. The trend is clearly moving toward issuance of so-called security token offerings: more and more ICO teams want to tie tokens to enforceable rights, which provide token owners with a legal position akin to that of shareholders. Thus, the vision of a capital market in which start-ups and SMEs are able to access needed growth capital without having to move offshore and which offers investors safe and simple access to diversification opportunities is coming within grasping distance.

This article presents legal challenges for effective blockchain-based capital markets in different countries by way of examples and in particular discusses the following subjects:

- Challenges posed by the classification of tokens in financial market regulations

- Legal preconditions for the issuance of security tokens

- Legal framework conditions for trading in security tokens

Classification of Tokens as Securities

Classification of tokens within the existing framework of civil law is already quite difficult and the opinions of legal scholars differ widely: for instance, in Switzerland it is debated whether tokens are digital assets, contractual rights, or a special form of assets in their own right.[1] This represents a difficult task for regulators with respect to a legal assessment in terms of financial legislation. Obligations under financial market regulations with respect to the issuance and trading of tokens directly depend on their legal classification. For example, if tokens are classified as securities[2] under a specific legal order, public offerings of such tokens without an appropriate prospectus may make issuers liable to criminal prosecution. Accordingly, correct classification is quite important, but it is anything but trivial: not unlike a blank sheet of paper, tokens can be configured with any combination of rights and obligations, or in the framework of smart contracts even with complex, automated processes. Various countries are trying to meet this challenge in very different ways:

Classification of tokens within the existing framework of civil law is already quite difficult and the opinions of legal scholars differ widely: for instance, in Switzerland it is debated whether tokens are digital assets, contractual rights, or a special form of assets in their own right.[6] This represents a difficult task for regulators with respect to a legal assessment in terms of financial legislation. Obligations under financial market regulations with respect to the issuance and trading of tokens directly depend on their legal classification. For example, if tokens are classified as securities[7] under a specific legal order, public offerings of such tokens without an appropriate prospectus may make issuers liable to criminal prosecution. Accordingly, correct classification is quite important, but it is anything but trivial: not unlike a blank sheet of paper, tokens can be configured with any combination of rights and obligations, or in the framework of smart contracts even with complex, automated processes. Various countries are trying to meet this challenge in very different ways:

The approach that has been historically established in US case law is based on flexible rather than static principles, which makes it possible to adapt regulations to the countless different possible designs.[8] This is primarily based on the Howey Test and the term security is tied to whether “an investment in a common venture is premised on a reasonable expectation of profits to be derived from the entrepreneurial or managerial efforts of others.” Whether there is indeed “a reasonable expectation of profit” is sometimes questionable, particularly in ICO projects which refrain from according any rights to investors. Supervisory authorities can strengthen legal certainty by regularly publicizing relevant rulings.

The legal situation in the EU is more formal. The EU directive on markets for financial instruments (better known as MiFID, or MiFID II) has largely harmonized financial markets in the single European market; the term “financial instrument” was defined in Annex I, section C. Unfortunately, it remains essentially unclear under what circumstances a security token is actually classified as a financial instrument. The definitions in the directive refer to “old world” terms (i. e. before blockchain technology), which simply cannot accommodate the plethora of possible designs associated with tokens. The Malta Financial Services Authority has at least attempted to provide some clarity in the form of a financial instrument test.[9] Without practical examples, the definitions nevertheless exhibit a degree of abstraction that leaves market participants unsure if tokens are deemed to represent financial instruments in view of the multitude of possible configurations.

The Swiss financial market supervisory authority Finma has decided on a compromise in its ICO guidelines.[10] Similar to the method adopted in the US, a functional approach is used with respect to investment purposes. At the same time, formal criteria are taken into account as well, and essentially every token that represents an asset is considered a security token. Due to these comparatively clear criteria and the possibility of asking Finma to provide regulatory information on specific cases in advance, the legal situation pertaining to various token configurations can be easily assessed in Switzerland.

The tokenization of traditional securities, such as stocks or bonds, is the easiest to assess: The laws were written for these types of securities and issuers are unlikely to face surprises with respect to tax consequences either. In order to prevent the erection of inappropriate barriers to innovation in virtual worlds and the tokenization of real assets, a restrictive application of the various terms designating securities would be welcome. For example, if one were to tokenize tickets to an event, such tokens may already be regarded as securities in several countries: for one thing, a real asset is underlying the token, for another thing one may well purchase event tickets for investment purposes, i. e. in the hope of being able to sell them at a higher price at a later date. At the same time, it seems hardly appropriate to having to issue a prospectus or to trade such tokens on a regulated exchange.

Primary Market: Issuance of Security Tokens

From a technical perspective, the internet makes it easy to market token offerings globally, and cryptocurrencies allow investors to buy tokens globally. Expensive intermediaries such as investment banks are barely needed anymore. The rapid growth of ICOs demonstrates that such a global capital market offers highly attractive funding opportunities for companies. However, upon issuing security tokens one is faced with a patchwork of national regulations. The most important aspect in this context: potential prospectus obligations.

A prospectus is intended to provide investors with the information required to make an investment decision. What information precisely has to be included varies from country to country and ranges from (for the time being) a few pages in Switzerland to almost book-sized tomes in the US. Prospectus requirements in the EU are so demanding that small funding rounds are barely worth the investment of time and money needed to draw up and publish a company’s financial statements. As an illustration of the costs involved: according to the Official Journal of the EU, the cost of drawing up an EU prospectus for offers of securities to the public with a total consideration of less than € 1,000,000 is likely to be disproportionate to the proceeds.[11] And that is just the prospectus for the EU. For every additional country in which tokens are to be offered, one has to verify whether a prospectus needs to be published and/or has to be reviewed by the local authorities.

Prospectus obligations may be limited or waived entirely below a certain threshold and plans by a number of countries to raise such thresholds for prospectus publication obligations have to be welcomed in this context (in the EU to around EUR 8 million or in Switzerland to CHF 2.5 million). Further relief is to be provided by various exemptions, such as thresholds on the number of investors or the focus on professional or accredited investors. While prospectus obligations and restrictions on distribution represent barriers to security token offerings, there already exist numerous projects which are able to implement such offerings successfully and with legal certainty. Along with growing interest, the required know-how will spread in the marketplace and costs will be lowered further, not least through the use of legal-tech software for drawing up documentation in various countries.

Secondary Markets: Trading in Security Tokens

The most impressive efficiency gains are possible in trading. Thanks to smart contracts, so-called decentralized trading platforms can be built, which enable trading between two parties without any intermediaries or counterparty risks. The assets to be traded are safely stored via the smart contract, and once the required conditions are fulfilled, clearing and settlement takes place automatically on the blockchain. Infrastructure costs, such as centralized security depositories, security settlement systems, or banks, and counterparty risks disappear. It is simply not possible in such a system to be affected by a default such as that of Lehman Brothers.

A sensible function that remains in place consists of match-making platforms similar to those operated by stock exchanges or other trading platforms, which are in particular aimed at efficient price formation and the prevention of market abuse. From a regulatory perspective, risks, such as insider trading and market manipulation, remain extant in the blockchain world as well, and modern-day regulations are in essence applicable to trading platforms for security tokens. In the meantime, both established exchanges such Switzerland’s SIX[12] and blockchain enterprises in a number of countries have made public announcements regarding the development of security token trading platforms. As “old-world” regulations remain applicable, a license is necessary, which has so far not been granted in any (developed) country. Moreover, the focus of proposed or already implemented blockchain-related legislation in various countries is on cryptocurrency trading and on utility tokens – which has largely no effect on the regulation of security token trading venues. Nevertheless, advisory practices and press releases by numerous enterprises in the industry give cause for confidence that trading venues for security tokens will be established shortly. After all, for ICO teams the tradability of a token is an important criterion affecting its design.

Final Remarks

The consummate ease with which tokens can be issued, transferred, and equipped with automated payment functions could be the basis for an “internet of finance” – a new generation of financial markets in which even the smallest projects can quickly and safely obtain external funding without intermediaries. Imagine for example a small bakery in a village which can get funding for a new oven from its loyal customers by issuing a tokenized micro-bond with automated interest payment features, or a movie project which automatically pays out a share of its revenue to the community of fans that funded it with every download. The indirect interaction between capital seekers and capital suppliers makes not only large, global funding rounds possible but also promotes stronger relationships between small investors and their local economy.

Moreover, a blockchain-based, decentralized trading system provides greater stability and safety, as the absence of intermediaries removes potential points of failure and middlemen whose incentives are not necessarily aligned with those of investors. In order for this technology to achieve its full potential for creating an attractive capital market for companies and investors, existing regulations have to be applied with sound judgment and a sense of proportion. Luckily the legislative pendulum is currently swinging toward deregulation again, and more and more regulatory exemptions are planned, particularly for start-up companies and small and medium-sized enterprises.[13] However, in order to make it possible for unicorns and already successful companies to obtain adequate funding in their home markets, more than exemptions for small projects will be needed. In a global financial market characterized by mobile talent, courage on the part of regulators to open up and liberalize markets stands to be rewarded.

[1] See “EU: €2.1 billion to boost venture capital investment in Europe’s innovative start-ups” [press release], European Commission, April 10, 2018.

[2] See Building a proportionate regulatory environment to support SME listing [public consultation], European Commission, 2017.

[3] Figures according to Coindesk ICO Tracker, accessed September 19, 2018.

[4] Figures according to CoinMarketCap, accessed September 19, 2018.

[5] See “Digital Tulips? Returns to Investors in Initial Coin Offerings,” Hugo Benedetti and Leonard Kostovetsky, SSRN, May 20, 2018.

[6] See “Verfügungsmacht und Verfügungsrecht an Bitcoins im Konkurs” (“Authority to dispose of and right to dispose of Bitcoins in insolvency proceedings”), Christian Meisser, Luzius Meisser, and Ronald Kogens, Jusletter IT: online, May 24, 2018.

[7] The term security is used as an overarching term herein for all designations of a similar type used in different jurisdictions, such as stocks/bonds or financial instruments.

[8] See Report of Investigation Pursuant to Section 21(a) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934: The DAO, Securities and Exchange Commission, Release No. 81207, July 25, 2017

[9] See Guidance Note To The Financial Instrument Test, Malta Financial Services Authority, July 24, 2018.

[10] See Guidelines for enquiries regarding the regulatory framework for initial coin offerings (ICOs), Finma, February 16, 2018.

[11] See “REGULATION (EU) 2017/1129 OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL of 14 June 2017 on the prospectus to be published when securities are offered to the public or admitted to trading on a regulated market (prospectus directive 3),” European Union, Official Journal of the European Union, June 30, 2017.

[12] See “SIX to launch full end-to-end and fully integrated digital asset trading, settlements and custody training” [press release], SIX Group AG, July 6, 2018.

[13] See “Fact Sheet Frequently asked questions: Easier access to financing for smaller businesses through capital markets” [press release], European Commission, May 24, 2018.